Education

The practice of medicine is arduous and ever changing. This is never more true than in the realm of infectious diseases where the microorganisms themselves are continuously evolving. On an ongoing basis the Antibiotic Stewardship team is developing educational material and updates on new trends and developments in the use of antimicrobials and ID diagnostics both at UC Davis and nationwide.

What’s Unique?

We screen all eligible adult patients upon admission for Clostridioides difficile (formerly Clostridium difficile, AKA C diff) with a rectal swab PCR test. This test looks for C diff capable of producing toxin. It identifies colonization, not disease. Colonized patients are at greater risk for disease and transmission.

Things to know…

- A positive screening test should not be used for diagnosis and does not require a follow up diagnostic test in the absence of symptoms consistent with C diff infection (CDI)

- Colonized patients will be placed on “Contact Enteric” precautions for the duration of their hospital stay

- In the absence of CDI, colonized patients do not need to continue isolation precautions upon discharge or transfer to another facility

- Hand washing with soap and water is necessary for both colonized and infected patients to further reduce transmission

What’s the Same?

Everything else.

- Diagnostic testing with the “C diff Diagnostic Test” is diagnostic in patients with signs and symptoms compatible with CDI. False positives are still possible, however, if:

- <3 watery BMs/day… on stool softeners… on tube feeds… other causes of diarrhea present

- Given increases in community-onset C diff infection (CO-CDI) without traditional risk factors consider early diagnostic testing in those admitted complaining of diarrhea even if at low to moderate risk

- There is no utility in tests for cure or repeat testing if < 7 days from last negative test

- Most cases of CDI can be treated with: Vancomycin 125 mg PO q6h x 10 days.

- Further guidance for recurrent or severe disease available in the 2018 IDSA guidelines

Antibiotics save lives, but too many antibiotics can also shorten them. With increasing evidence that the rate of acute kidney injury, Clostridioides difficile, and subsequent multidrug resistant infections increase with every additional day of antimicrobial therapy it is essential that correct antibiotic duration be given in addition to the correct antibiotic.

Attached below are three PDFs highlighting the current guidance on appropriate antibiotic duration for common, uncomplicated infections in adults.

Procalcitonin (PCT) is a biomarker of bacterial infection shown to reliably guide antibiotic use in some cases. It is acutely produced by a number of tissue types in response to bacterial toxins and various inflammatory mediators associated with bacterial but not viral infection. In some bacterial infections, particularly mild, localized disease, significant procalcitonin production may not occur. PCT therefore does not completely discriminate the presence or absence of a possible bacterial pathogen in all cases. PCT does, however, correlate with disease severity and may help discriminate those patients who would benefit from antibiotics from those who would not in some circumstances. Although it has been studied in a wide variety of populations, it has to date only been shown to consistently and safely guide clinicians in the initiation of antibiotics in non-septic patients with a clinically ambiguous lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) and in the discontinuation of antibiotics in septic patients without a clear source of infection identified. Further guidance per below:

The BioFire and GenMark systems at UC Davis Medical Center are important tools for the timely diagnosis and identification common infections including bacteremia, respiratory infections, gastroenteritis, and meningoencephalitis. As with any tool they have certain strengths and limitations dependent on the contexts in which it is ordered and how it is used. All of the BioFire and GenMark panels have significant financial costs which should preclude their routine use for uncomplicated disease processes. The following are some clinical guidance on the optimal use of our various BioFire systems:

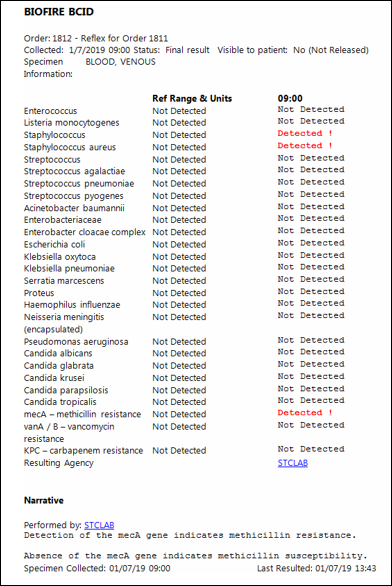

Blood Culture Identification (BCID) Panel (by BioFire) -

The BCID report appears in Epic attached to blood culture reports as to the right. If a target is detected and is consistent with gram stain results identification is accurate in the great majority of circumstances. Because the BCID panel can detect DNA primers at a higher taxonomic level for some organisms (at the genus and family and not just species), multiple flags may sometimes fire leading to results that may be difficult to interpret. In the example to the right, both "Staphylococcus" and "Staphylococcus aureus" fired because the DNA primers for both Staphylococci in general and Staphylococcus aureus more specifically were detected. If only the "Staphylococcus" target had been detected in the absence of the "Staphylococcus aureus" target it is likely the organism would have eventually be identified by conventional means as a coagulase-negative Staph (CoNS). Similar phenomena may occur with the "Streptococcus" and "Enterobacteriaceae" genus targets. As another example a positive "Enterobacteriaceae" in the absence of any other flags firing likely indicates a gram negative organism present within the family Enterobacteriaceae but not one of the Enterobacteriaceae targeted (i.e. E. cloaecae, E. coli, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, or Proteus) where as a blood culture with both an "Enterobacteriaceae" and a "Proteus" flag firing is most likely due to presence a Proteus species alone. Also of note in the first example pictured right, the mecA gene was detected indicating this Staphylococcus aureus isolate is most likely methicillin-resistant, or MRSA.

The BCID report appears in Epic attached to blood culture reports as to the right. If a target is detected and is consistent with gram stain results identification is accurate in the great majority of circumstances. Because the BCID panel can detect DNA primers at a higher taxonomic level for some organisms (at the genus and family and not just species), multiple flags may sometimes fire leading to results that may be difficult to interpret. In the example to the right, both "Staphylococcus" and "Staphylococcus aureus" fired because the DNA primers for both Staphylococci in general and Staphylococcus aureus more specifically were detected. If only the "Staphylococcus" target had been detected in the absence of the "Staphylococcus aureus" target it is likely the organism would have eventually be identified by conventional means as a coagulase-negative Staph (CoNS). Similar phenomena may occur with the "Streptococcus" and "Enterobacteriaceae" genus targets. As another example a positive "Enterobacteriaceae" in the absence of any other flags firing likely indicates a gram negative organism present within the family Enterobacteriaceae but not one of the Enterobacteriaceae targeted (i.e. E. cloaecae, E. coli, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, S. marcescens, or Proteus) where as a blood culture with both an "Enterobacteriaceae" and a "Proteus" flag firing is most likely due to presence a Proteus species alone. Also of note in the first example pictured right, the mecA gene was detected indicating this Staphylococcus aureus isolate is most likely methicillin-resistant, or MRSA.

If a polymicrobial infection or process is not suspected, antibiotics may be narrowed to target the identified organism in the great majority of cases. Conversely, in a patient without clear signs or symptoms of infection but with a single blood culture bottle growing gram positive cocci and only the "Staphylococcus" flag firing, antibiotics can likely be avoided as the blood culture is likely to grow out CoNS consistent with contamination

Pathogens include:

Respiratory Panel (by GenMark) -

Pathogens include:

Gastrointestinal (GI) Panel (by BioFire) -

Pathogens include:

Meningoencephalitis (ME) Panel (by BioFire) -

Pathogens include:

What is asymptomatic bacteriuria?

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is technically defined as a urine culture growing ≥ 10^5 colony-forming units/mL of a single organism from a clean-catch voided urine sample. In women the recommendation is for this to be repeated as rates of transient bacteriuria are higher. Catheterized specimens more consistently reflect what is happening within the bladder so a repeat sample is not necessary for men or women. In all cases the patient has no signs or symptoms consistent with a urinary tract infection (UTI).

From a practical perspective the magnitude of the bacteriuria is typically of less practical value because in the absence of symptoms the clinical management is the same. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is not associated with significantly greater morbidity or mortality than a sterile bladder, and the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria has not been shown to be helpful in the great majority of cases.

What counts as a symptom?

Dysuria, urinary frequency or urgency, suprapubic or flank pain, and costovertebral angle tenderness are common signs and symptoms reported with UTIs. Delirium and congitive changes in the absence of these and in the absence of fever or hemodynamic instability suggestive of systemic infection are typically not considered symptoms. Guidelines have consistently recommended against up front treatment for patients such as these unless other causes have been ruled out and the cognitive changes persist after a period of observation.

Notably the CDC also explicitly recommends against urine culturing for:

- Malodorous urine

- Cloudy urine

- As a reflex to pyuria alone

Will antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria help my patient?

No. In fact, antibiotic treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria will only *hurt* your patient. Multiple studies in multiple different patient populations have revealed *no benefit* from the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. Antibiotic treatment did not prevent future UTIs, sepsis, hospitalization, progression of kidney disease, or death. Antibiotic treatment was, however, associated with the selection of more resistant organisms when the next UTI did occur.

The only exceptions to this rule are pregnant women, those about to undergo a urologic procedure, and some patients shortly after kidney transplantation. These individuals *should* be treated for their asymptomatic bacteriuria as in these populations it has been shown to prevent future complications.

What about the pyuria?

Pyuria predicts the presence of bacteriuria, but it does not change the clinical context of the bacteriuria. Although a urinalysis with elevated white blood cells is more likely than one that does not to have a significant amount of bacteria in culture, if the urine was obtained from a patient without signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI its clinical significance is trumped by the absence of symptoms. Asymptomatic bacteriuria has the same prognosis regardless of the presence of urinary white blood cells.

What about nitrites?

Nitrites predict the presence of gram negative, predominately Entoerbacteriaceae, bacteriuria, but, as with pyuria, do not change its clinical context. The patient is more likely to have a positive urine culture, but is no more likely to benefit from antibiotics in the absence of symptoms than if their urine was sterile.

How do bladder cathethers factor into all this?

Bladder catheters significantly increase the risk for UTIs, but the signs and symptoms indicative of a UTI are largely the same in most patient populations (primarily excluding spinal cord injury patients). Notably, many findings are common and do not consistently indicate a UTI including cloudy urine, foul smelling urine, and urinary sediment. It is unclear to what extent these findings can predict the presence of bacteriuria, but regardless in the absence of clinical signs and symptoms of a UTI there is *no* indication for treatment as there is *no* benefit to be obtained from antibiotic therapy. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, part of the Department of Health and Human Services, has released an excellent webinar regarding UTIs in cathterized patients.

Where can I get more information?

The Infectious Disease Society of America released updated guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic bacteriuria this year. They can be referenced at:

IV antibiotics often come with more than just the antibiotic. Sodium is a significant portion of the carrier fluid in many IV ready to use (RTU) formulations or in the IV fluid diluent necessary for the administration of many intravenous antibiotics. In some cases, the amount of sodium infused can exceed 2 g per a day making the treatment of many conditions, congestive heart failure to name just one, significantly more difficult to manage. Yet another reason to switch from IV to PO when it's safe to do so.

UC Davis ASP has partnered with Firstline to provide UC Davis-specific antimicrobial guidance through Firstline's free app.

UC Davis ASP has partnered with Firstline to provide UC Davis-specific antimicrobial guidance through Firstline's free app.