Resident Program - Case of the Month

July 2022 – Presented by Dr. Alexander Ladenheim (Mentored by Dr. Tony Karnezis)

Discussion

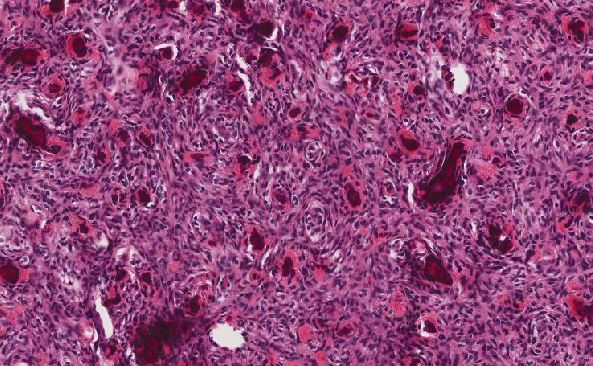

Endometrial adenocarcinoma with invasion into the cervical stroma has a significantly worse prognosis than disease confined to the uterine corpus. As such, correct diagnosis is paramount. However, this is complicated by a well-documented tendency for the invasive component in the cervix to appear morphologically distinct from the uterine corpus component; and moreover, for this invasive component to appear deceptively bland. Tambouret et al. describe this pattern of invasion as “burrowing” (1). They note that there is frequently no gross or microscopic involvement of the cervical surface epithelium by carcinoma. The invasive carcinoma often infiltrates deeply into the cervical stroma, as in this case, and paradoxically this can occur in cases where the uterine corpus tumor shows no or minimal myometrial invasion.

The differential diagnosis includes all of the entities listed previously. There are variants of endocervical adenocarcinoma (A) which can be deceptively bland, such as minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA; adenoma malignum) or mesonephric type, with a predominately tubular pattern and widely spaced malignant glands. The likelihood of a synchronous endocervical adenocarcinoma is admittedly low, but this scenario is certainly not impossible. Immunohistochemical staining can be of aid to distinguish between these entities. Typically, MDA would be expected to show positive staining for CEA and a mutant p53 staining pattern, with negative staining for ER and vimentin. Although MDA is not thought to be HPV-mediated, other endocervical adenocarcinomas are and would show diffuse, strong p16 expression (2). In endometrial adenocarcinoma, the opposite staining pattern (ER+/vimentin+/CEA neg/p16 neg/p53 wild-type) is more common, as seen in our case.

Endosalpingiosis (C), the ectopic localization of endometrial glands into the cervix, and tubal metaplasia of endocervical glands are challenging differential diagnoses. The glands in endosalpingiosis would be expected to be found usually in the outer half of the cervical stroma. In both conditions, they would be less infiltrative, more organized, and have no cytologic atypia. In the present case, the glands were deeply infiltrative, haphazard, had cytologic and nuclear atypia, and had abnormal localization adjacent to cervical stromal vessels, which is more compatible with malignancy.

Although most immunohistochemical markers would not differentiate endosalpingiosis, tubal metaplasia, and endometrial adenocarcinoma, by luck in this case, the tumor both in the corpus and cervix showed MLH1 loss, which is both an abnormal molecular event that would not occur in benign proliferations and strong evidence for a relationship between the corpus and cervical components. Other potentially useful IHC markers for establishing a relationship between an endometrial cancer and glands suspicious for cervical involvement include loss of expression of ARID1A and/or PTEN (3, 4). These stains, like the MMR protein IHCs, are also IHC surrogates for molecular alterations which occur frequently in endometrioid adenocarcinoma. It must be borne in mind that these molecular alterations, although fairly specific for endometroid adenocarcinoma in the context of gynecologic malignancies, are not sensitive (only occur in 30-50% of cases), and outside of this context can occur in many other malignancies.

The small, tubular glands could also be mistaken for hyperplasia of mesonephric remnants (D). However, mesonephric remnants tend to have flat, cuboidal epithelium and have dense, eosinophilic luminal secretions. IHC staining is helpful in its distinction from endometrial adenocarcinoma, as mesonephric remnants are positive for GATA3, TTF-1, CD10, and calretinin, and they are typically negative for hormone receptors (5).

Tunnel clusters (E) are benign proliferations of endocervical glands. These would typically be located close to the surface of the cervix and maintain organization with a lobular pattern, unlike what is seen in the present case. The IHC findings supportive of endometrial origin and MLH1 loss also help exclude tunnel clusters.

References

- Tambouret R, Clement PB, Young RH. Endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma with a deceptive pattern of spread to the uterine cervix: a manifestation of stage IIb endometrial carcinoma liable to be misinterpreted as an independent carcinoma or a benign lesion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003 Aug;27(8):1080-8. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00005

- Houghton O, Jamison J, Wilson R, Carson J, McCluggage WG. p16 Immunoreactivity in unusual types of cervical adenocarcinoma does not reflect human papillomavirus infection. Histopathology. 2010 Sep;57(3):342-50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03632.x

- Garg K, Broaddus RR, Soslow RA, Urbauer DL, Levine DA, Djordjevic B. Pathologic scoring of PTEN immunohistochemistry in endometrial carcinoma is highly reproducible. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2012 Jan;31(1):48-56. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0b013e3182230d00

- Guan B, Mao TL, Panuganti PK, Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Maeda D, Chen E, Jeng YM, Wang TL, Shih IeM. Mutation and loss of expression of ARID1A in uterine low-grade endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011 May;35(5):625-32. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318212782a

- Pors J, Cheng A, Leo JM, Kinloch MA, Gilks B, Hoang L. A Comparison of GATA3, TTF1, CD10, and Calretinin in Identifying Mesonephric and Mesonephric-like Carcinomas of the Gynecologic Tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018 Dec;42(12):1596-1606. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001142

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director

LeShelle May

LeShelle May Chancellor Gary May

Chancellor Gary May