Explanation of Coccidioides Diagnostic Testing

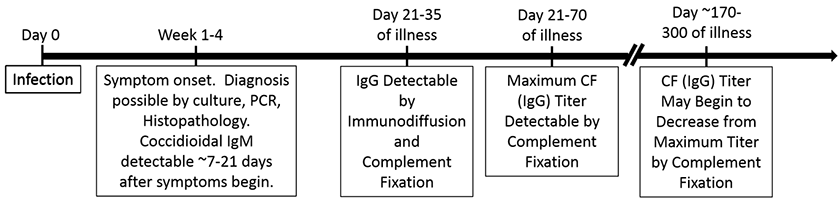

Diagnosis of Valley Fever can involve culture or nucleic-acid-based detection from respiratory specimens, spherule detection in tissue samples by histopathology (HP), or by detection of specific antibodies in a patient’s serum or body fluid. Unfortunately, Coccidioides, the fungus that causes Valley Fever, is not often detectable in respiratory specimens and diagnosis is thus often made by serology – avoiding more invasive means of obtaining a diagnosis. Below is a timeline outlining a ‘typical’ Valley Fever disease course.

Note, however, that not all patients develop a detectable coccidioidal complement fixation titer. We estimate that roughly 15% of patients with serologically confirmed valley fever never develop a detectable complement fixation titer because patients with less severe disease do not develop significant IgG antibody titers (the complement fixation test is less sensitive than other serologic methods). The common misconception that complement fixation is a ‘confirmatory test’ for Valley Fever is false.

The UC Davis Coccidioidomycosis Serology lab performs coccidioidal immunodiffusion and complement fixation, which comprise a sensitive and specific repertoire for Valley Fever diagnosis and disease monitoring. The following is a basic explanation of each test.

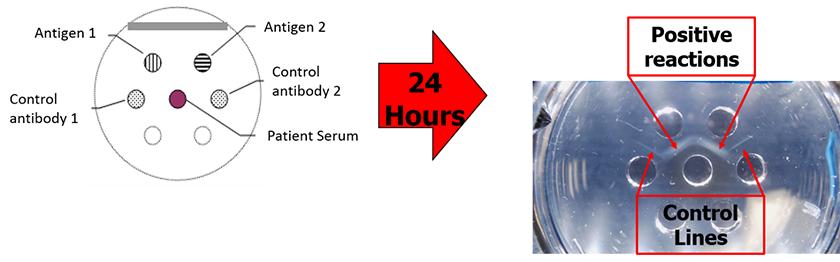

Immunodiffusion is a serum-based diagnostic that identifies specific antibodies in a patient’s serum. The test relies on the ability of antibodies and antigens in different wells of a gellan plate to diffuse into the gel and form a visible precipitation band at their intersection point. When performed in an experienced lab, this test is highly sensitive for the detection of Coccidioides-specific antibodies and thus the diagnosis of Valley Fever. We use this test to detect both coccidioidal IgM (sometimes referred to as coccidioidal precipitins) and IgG (sometimes referred to as coccidioidal CF or Complement Fixation) antibodies.

Complement fixation is a serum-based test that is used to roughly quantitate the amount of specific IgG antibody in a patient’s serum. The test relies on two intrinsic properties of complement, a serum component found in vertebrates that is involved in innate immunity:

- Complement will lyse sensitized (hemolysin treated) red blood cells.

- Complement will bind the Fc portion of IgG antibodies if and only if the antibodies are bound to antigens (which is a fundamental function of an antibody). Complement that is bound by antibodies will NOT lyse sensitized red blood cells.

Thus, we can add red blood cells to mixtures of patient serum, coccidioidal antigen, and complement to determine if specific antibodies to those coccidioidal antigens are present in the serum. If serum containing coccidioidal IgG antibodies (i.e. from a patient with Valley Fever) are mixed with coccidioidal antigen and complement, the resulting mixture containing complement-IgG-antigen complexes will NOT lyse red blood cells.

Conversely, if patient serum lacking coccidioidal IgG antibodies (i.e. someone not suffering from Valley Fever) is incubated with coccidioidal antigen and complement there will be no IgG-antigen complexes, no IgG-complement complexes, and the mixture WILL lyse red blood cells. In short, a complement fixation test tube with lysed red blood cells does not contain coccidioidal antibody and is reported as a ‘Negative’ result.

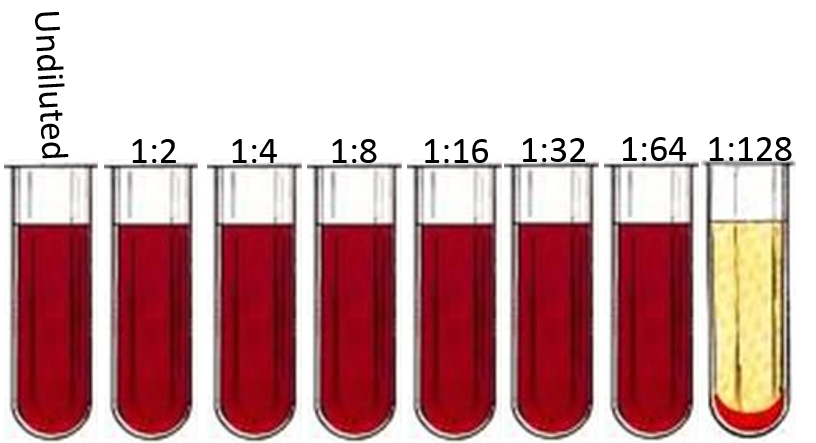

To arrive at a titer, positive serum samples can then be serially diluted and subjected to the same test to find the highest concentration of serum that fails to lyse red blood cells. The following is an illustration of a complement fixation test performed on 2-fold dilutions of a single serum specimen. The final ‘positive’ reaction (i.e. the last tube without lysed red blood cells) is 1:64, so the coccidioidal IgG antibody titer would be reported as 1:64.

Karryn Doyle, CCEP

Karryn Doyle, CCEP