Leukemia

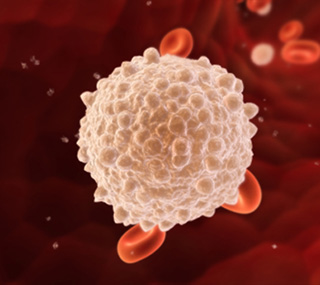

Leukemia occurs when the bone marrow makes abnormal white blood cells. Leukemia, the most common blood cancer, includes several diseases. The four major types are acute lymphocytic leukemia (also called acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), and chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML).

The Leukemia, Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma program at UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center is the largest and most comprehensive program of its kind in inland Northern California. It provides the most advanced methods of diagnosis and treatment possible, including new therapies that often aren't available at community hospitals.

The physicians in our leukemia program have extensive experience treating both common and uncommon cancers of the blood.

Throughout treatment, our patients have access to the latest technology, including an in-house cytogenetics lab that allows us to study chromosomes in order to provide individualized treatment based on a person's genes. In our bone marrow lab, each specimen is independently reviewed by two specialists, one in pathology and one in hematology and oncology.

Doctors sometimes find leukemia after a routine blood test. If you have symptoms that suggest leukemia, your doctor will try to find out what's causing the problems. Your doctor may ask about your personal and family medical history.

You may have one or more of the following tests:

Physical exam: Your doctor checks for swollen lymph nodes, spleen, or liver.

Blood tests: The lab does a complete blood count to check the number of white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets. Leukemia causes a very high level of white blood cells. It may also cause low levels of platelets and hemoglobin, which is found inside red blood cells.

Biopsy: Your doctor removes tissue to look for cancer cells. A biopsy is the only sure way to know whether leukemia cells are in your bone marrow. Before the sample is taken, local anesthesia is used to numb the area. This helps reduce the pain. Your doctor removes some bone marrow from your hipbone or another large bone. A pathologist uses a microscope to check the tissue for leukemia cells.

There are two ways your doctor can obtain bone marrow. Some people will have both procedures during the same visit:

Bone marrow aspiration: The doctor uses a thick, hollow needle to remove samples of bone marrow.

Bone marrow biopsy: The doctor uses a very thick, hollow needle to remove a small piece of bone and bone marrow.

Other Tests

The tests that your doctor orders for you depend on your symptoms and type of leukemia. You may have other tests:

Cytogenetics: The lab looks at the chromosomes of cells from samples of blood, bone marrow, or lymph nodes. If abnormal chromosomes are found, the test can show what type of leukemia you have. For example, people with CML have an abnormal chromosome called the Philadelphia chromosome.

Molecular genetic studies: At the time of diagnosis, your doctor may recommend running laboratory tests to identify specific genes, proteins and other factors involved in the leukemia. Examining the genes in leukemia cells is crucial to establishing a proper diagnosis and treatment plan. Acute Myeloid leukemia, for example, is caused by a buildup of mistakes (also called mutations) in the genes. Identifying these mistakes helps diagnose the specific subtype of AML and choose appropriate treatment options, such as more or less chemotherapy and/or stem cell transplantation. Many cancer clinical trials are currently evaluating the effectiveness of promising new drugs that target specific AML mutations. Identification of specific mutations may make some patients eligible for participation in these studies, and give them access to the most advanced treatment options available. For example, patients with an FLT3-ITD mutation, one of the most common molecular abnormalities in adult AML, may be eligible for a study that uses quizartinib, a new drug that targets the FLT3 mutation and blocks the genetic change that drives the AML. Molecular genetic tests are performed on bone marrow or blood samples.

Spinal tap: Your doctor may remove some of the cerebrospinal fluid (the fluid that fills the spaces in and around the brain and spinal cord). The doctor uses a long, thin needle to remove fluid from the lower spine. The procedure takes about 30 minutes and is performed with local anesthesia. You must lie flat for several hours afterward to keep from getting a headache. The lab checks the fluid for leukemia cells or other signs of problems.

Chest x-ray: An x-ray can show swollen lymph nodes or other signs of disease in your chest.

Sources: National Cancer Institute and UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

Like all blood cells, leukemia cells travel through the body. The symptoms of leukemia depend on the number of leukemia cells and where these cells collect in the body.

People with chronic leukemia may not have symptoms. The doctor may find the disease during a routine blood test.

People with acute leukemia usually go to their doctor because they feel sick. If the brain is affected, they may have headaches, vomiting, confusion, loss of muscle control, or seizures. Leukemia also can affect other parts of the body such as the digestive tract, kidneys, lungs, heart, or testes.

Common symptoms of chronic or acute leukemia may include:

- Swollen lymph nodes that usually don't hurt (especially lymph nodes in the neck or armpit)

- Fevers or night sweats

- Frequent infections

- Feeling weak or tired

- Bleeding and bruising easily (bleeding gums, purplish patches in the skin, or tiny red spots under the skin)

- Swelling or discomfort in the abdomen (from a swollen spleen or liver)

- Weight loss for no known reason

- Pain in the bones or joints

Most often, these symptoms are not due to cancer. An infection or other health problems may also cause these symptoms. Only a doctor can tell for sure.

Anyone with these symptoms should tell the doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Sources: National Cancer Institute and UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

The risk factors may be different for the different types of leukemia:

- Radiation: People exposed to very high levels of radiation are much more likely than others to get acute myeloid leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, or acute lymphocytic leukemia.

- Atomic bomb explosions: Very high levels of radiation have been caused by atomic bomb explosions (such as those in Japan during World War II). People, especially children, who survive atomic bomb explosions, are at increased risk of leukemia.

- Radiation therapy: Another source of exposure to high levels of radiation is medical treatment for cancer and other conditions. Radiation therapy can increase the risk of leukemia.

- Diagnostic x-rays: Dental x-rays and other diagnostic x-rays (such as CT scans - computerized tomography) expose people to much lower levels of radiation. It's not known yet whether this low level of radiation to children or adults is linked to leukemia. Researchers are studying whether having many x-rays may increase the risk of leukemia. They are also studying whether CT scans during childhood are linked with increased risk of developing leukemia.

- Smoking: Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of acute myeloid leukemia.

- Benzene: Exposure to benzene in the workplace can cause acute myeloid leukemia. It may also cause chronic myeloid leukemia or acute lymphocytic leukemia. Benzene is used widely in the chemical industry. It's also found in cigarette smoke and gasoline.

- Chemotherapy: Cancer patients treated with certain types of cancer-fighting drugs sometimes later get acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphocytic leukemia. For example, being treated with drugs known as alkylating agents or topoisomerase inhibitors is linked with a small chance of later developing acute leukemia.

- Down syndrome and certain other inherited diseases: Down syndrome and certain other inherited diseases increase the risk of developing acute leukemia.

- Myelodysplastic syndrome and certain other blood disorders: People with certain blood disorders are at increased risk of acute myeloid leukemia.

- Human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-I): People with HTLV-I infection are at increased risk of a rare type of leukemia known as adult T-cell leukemia. Although the HTLV-I virus may cause this rare disease, adult T-cell leukemia and other types of leukemia are not contagious.

- Family history of leukemia: It's rare for more than one person in a family to have leukemia. When it does happen, it's most likely to involve chronic lymphocytic leukemia. However, only a few people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia have a father, mother, brother, sister, or child who also has the disease.

- Age: age is an important risk factor for the development of leukemia. Most cases of acute myeloid leukemia and chronic lymphocytic leukemia are diagnosed in people over the age of 60. Conversely, acute lymphoblastic leukemia is the most common childhood cancer. It most commonly affects children under 4 years of age, although the risk also does increase in people over the age of 60.

Having one or more risk factors does not mean that a person will get leukemia. Most people who have risk factors never develop the disease.

Sources: National Cancer Institute and UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

People with leukemia have many treatment options. The options are watchful waiting, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, stem cell transplant and a rapidly developing group of targeted therapies, including immunotherapies. If your spleen is enlarged, your doctor may suggest surgery to remove it. Sometimes a combination of these treatments is used.

The choice of treatment depends mainly on the following:

- The type of leukemia (acute or chronic)

- Your age

- Whether leukemia cells were found in your cerebrospinal fluid

- Certain features of the leukemia cells

- Your symptoms and general health

People with acute leukemia need to be treated right away. The goal of treatment is to destroy signs of leukemia in the body and make symptoms go away. This is called a remission. After people go into remission, more therapy may be given to prevent a relapse. This type of therapy is called consolidation therapy or maintenance therapy. Many people with acute leukemia can be cured.

If you have chronic leukemia without symptoms, you may not need cancer treatment right away. Your doctor will watch your health closely so that treatment can start when you begin to have symptoms. Not getting cancer treatment right away is called watchful waiting.

When treatment for chronic leukemia is needed, it can often control the disease and its symptoms. People may receive maintenance therapy to help keep the cancer in remission, but chronic leukemia can seldom be cured with chemotherapy. However, stem cell transplants offer some people with chronic leukemia the chance for cure.

Your doctor can describe your treatment choices, the expected results, and the possible side effects. You and your doctor can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your medical and personal needs.

Tailored Treatments Through Clinical Trials

To ensure you receive the most effective and safest leukemia therapies currently available for your type of leukemia, your doctor may recommend participation in a clinical trial as the best treatment option. A clinical trial is a research study of new treatment methods. At UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, researchers are making great progress in understanding the many DNA changes that cause the disease and are developing novel treatments and personalized drugs designed to specifically target different types of leukemia cells. The close collaboration among our doctors and research scientists means that treatments developed in the laboratory can quickly move to the clinic, offering our patients immediate access to the latest therapies.

Led by a team of leukemia specialists, including Brian Jonas, Jeanna Welborn, Mehrdad Abedi, Joseph Tuscano and Carol Richman.

For a complete list of clinical studies, please visit Adult Clinical Trials for UC Davis.

Talk to your doctor or contact a navigator to learn more about our clinical trials program, and for a list of leukemia clinical studies accepting participants in your area, visit the National Cancer Institute.

Watchful Waiting

People with chronic lymphocytic leukemia who do not have symptoms may be able to put off having cancer treatment. By delaying treatment, they can avoid the side effects of treatment until they have symptoms.

If you and your doctor agree that watchful waiting is a good idea, you'll have regular checkups (such as every 3-6 months). You can start treatment if symptoms occur.

Although watchful waiting avoids or delays the side effects of cancer treatment, this choice has risks. It may reduce the chance to control leukemia before it gets worse.

You may decide against watchful waiting if you don't want to live with an untreated leukemia. Some people choose to treat the cancer right away.

If you choose watchful waiting but grow concerned later, you should discuss your feelings with your doctor. A different approach is nearly always available.

Chemotherapy

Many people with leukemia are treated with chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to destroy leukemia cells. Depending on the type of leukemia, you may receive a single drug or a combination of two or more drugs.

You may receive chemotherapy in several different ways:

- By mouth: Some drugs are pills that you can swallow.

- Into a vein (IV ): The drug is given through a needle or tube inserted into a vein.

- Through a catheter (a thin, flexible tube): The tube is placed in a large vein, often in the upper chest. A tube that stays in place is useful for patients who need many IV treatments. The health care professional injects drugs into the catheter, rather than directly into a vein. This method avoids the need for many injections, which can cause discomfort and injure the veins and skin.

- Into the cerebrospinal fluid: If the pathologist finds leukemia cells in the fluid that fills the spaces in and around the brain and spinal cord, the doctor may order intrathecal chemotherapy. The doctor injects drugs directly into the cerebrospinal fluid. Intrathecal chemotherapy is given in two ways:

- Into the spinal fluid: The doctor injects the drugs into the spinal fluid.

- Under the scalp: Children and some adult patients receive chemotherapy through a special catheter called an Ommaya reservoir. The doctor places the catheter under the scalp. The doctor injects the drugs into the catheter. This method avoids the pain of injections into the spinal fluid.

Intrathecal chemotherapy is used because many drugs given by IV or taken by mouth can't pass through the tightly packed blood vessel walls found in the brain and spinal cord. This network of blood vessels is known as the blood-brain barrier.

Chemotherapy is usually given in cycles. Each cycle has a treatment period followed by a rest period.

You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor's office, or at home. Some people may need to stay in the hospital for treatment.

The side effects depend mainly on which drugs are given and how much. Chemotherapy kills fast-growing leukemia cells, but the drug can also harm normal cells that divide rapidly:

- Blood cells: When chemotherapy lowers the levels of healthy blood cells, you're more likely to get infections, bruise or bleed easily, and feel very weak and tired. You'll get blood tests to check for low levels of blood cells. If your levels are low, your health care team may stop the chemotherapy for a while or reduce the dose of drug. There also are medicines that can help your body make new blood cells. Or, you may need a blood transfusion.

- Cells in hair roots: Chemotherapy may cause hair loss. If you lose your hair, it will grow back, but it may be somewhat different in color and texture.

- Cells that line the digestive tract: Chemotherapy can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Ask your health care team about medicines and other ways to help you cope with these problems.

- Sperm or egg cells: Some types of chemotherapy can cause infertility.

- Children: Most children treated for leukemia appear to have normal fertility when they grow up. However, depending on the drugs and doses used and the age of the patient, some boys and girls may be infertile as adults.

- Adult men: Chemotherapy may damage sperm cells. Men may stop making sperm. Because these changes to sperm may be permanent, some men have their sperm frozen and stored before treatment (sperm banking).

- Adult women: Chemotherapy may damage the ovaries. Women may have irregular menstrual periods or periods may stop altogether. Women may have symptoms of menopause, such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Women who may want to get pregnant in the future should ask their health care team about ways to preserve their eggs before treatment starts.

Targeted Therapy

Unlike chemotherapy drugs, which non-specifically attack cells that are rapidly dividing, targeted therapies are designed to kill only cancer cells, sparing healthy cells in the process. Often called "personalized medicine," targeted therapies use drugs that target and block the growth of leukemia cells. For example, a targeted therapy, such as the drug ibrutinib, may block the action of an abnormal protein that stimulates the growth of leukemia cells. Ibrutinib targets and attacks the BTK protein that causes chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Targeted therapies may cause a range of side effects such as decreased blood counts, nausea, bloating and muscle cramps. Your doctor will talk to you about what to expect and how to manage the symptoms. Your cancer care team will monitor you for signs of problems.

You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor's office or in the hospital. Other drugs may be given at the same time to prevent side effects.

Immunotherapies

Cancer cells grow uncontrollably by avoiding recognition by the immune system. However, a newer class of therapeutics, called immunotherapies, are designed to take advantage of the ways in which cancer cells evade the immune system. Immunotherapies activate the immune system to attack cancer cells by targeting proteins expressed on cancer cells or proteins abnormally expressed on immune cells.

For example, one type of immunotherapy, called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, has been effective in treating patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). In CAR T-cell therapy, T cells from a patient are removed and genetically modified to express a protein receptor that recognizes a particular antigen found on leukemia cells. The receptor is called “chimeric” because it is not naturally found on T cells. The genetically modified T cells are then put back into the patient so his or her immune system can begin fighting the cancer.

Immunotherapy drugs are also being used to treat patients with leukemia. Blinatumomab, for example, treats patients with ALL by increasing the cancer-killing power of the immune system. Other immunotherapies release the brakes on the natural cancer-fighting power of the immune system. For example, PD-1 or PD-L1 antibodies are currently given to patients in clinical trials to turn on T cells, which play a crucial role in fighting the cancer, but have been turned off by the cancer.

Immunotherapies are used in the treatment of many types of leukemia and represent an exciting new frontier in blood cancer therapy.

Stem Cell Transplant

Some people with leukemia receive a stem cell transplant. A stem cell transplant allows you to be treated with high doses of drugs, radiation, or both. The high doses destroy both leukemia cells and normal blood cells in the bone marrow. After you receive high dose chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, you receive healthy stem cells through a large vein. (It's like getting a blood transfusion.) New blood cells develop from the transplanted stem cells. The new blood cells replace the ones that were destroyed by treatment.

Stem cell transplants take place in the hospital. Stem cells may come from you or from someone who donates their stem cells to you:

- From you: An autologous stem cell transplant uses your own stem cells. Before you get the high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy, your stem cells are removed. The cells may be treated to kill any leukemia cells present. Your stem cells are frozen and stored. After you receive high-dose chemotherapy or radiation therapy, the stored stem cells are thawed and returned to you.

- From a family member or other donor: An allogeneic stem cell transplant uses healthy stem cells from a donor. Your brother, sister, or parent may be the donor. Sometimes the stem cells come from a donor who isn't related. Doctors use blood tests to learn how closely a donor's cells match your cells. A transplant from a family member or an unrelated donor may also work as a form of immunotherapy by using the donor’s immune system to eliminate your leukemia cells. This is called graft-versus-leukemia effect.

Stem cells come from a few sources. The stem cells usually come from the blood (peripheral stem cell transplant). Or they can come from the bone marrow (bone marrow transplant). Another source of stem cells is umbilical cord blood. Cord blood is taken from a newborn baby and stored in a freezer. When a person gets cord blood, it's called an umbilical cord blood transplant.

After a stem cell transplant, you may stay in the hospital for several weeks or months. You'll be at risk for infections and bleeding because of the large doses of chemotherapy or radiation you received. In time, the transplanted stem cells will begin to produce healthy blood cells.

Another problem is that graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) may occur in people who receive donated stem cells. In GVHD, the donated white blood cells in the stem cell graft react against the patient's normal tissues. Most often, the liver, skin, or digestive tract is affected. GVHD can be mild or very severe. It can occur any time after the transplant, even years later. Steroids or other drugs may help. Visit our Stem Cell Transplant Program website to find answers to commonly asked questions regarding stem cell transplantation.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill leukemia cells. People receive radiation therapy at a hospital or clinic.

Some people receive radiation from a large machine that is aimed at the spleen, the brain, or other parts of the body where leukemia cells have collected. This type of therapy takes place 5 days a week for several weeks. Others may receive radiation that is directed to the whole body. The radiation treatments are given once or twice a day for a few days, usually before a stem cell transplant.

The side effects of radiation therapy depend mainly on the dose of radiation and the part of the body that is treated. For example, radiation to your abdomen can cause nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. In addition, your skin in the area being treated may become red, dry, and tender. You also may lose your hair in the treated area.

You are likely to be very tired during radiation therapy, especially after several weeks of treatment. Resting is important, but doctors usually advise patients to try to stay as active as they can.

Although the side effects of radiation therapy can be distressing, they can usually be treated or controlled. You can talk with your doctor about ways to ease these problems.

It may also help to know that, in most cases, the side effects are not permanent. However, you may want to discuss with your doctor the possible long-term effects of radiation treatment.

For more information about treatment options specific to each leukemia type, click on the following links at the National Cancer Institute:

- Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia/Other Myeloid Malignancies

- Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- Hairy Cell Leukemia

Sources: National Cancer Institute and UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

Hematology and Oncology

Mehrdad Abedi, M.D.

Mehrdad Abedi, M.D.

Professor of Internal Medicine, Hematology and Oncology

Brian A. Jonas, M.D., Ph.D.

Brian A. Jonas, M.D., Ph.D.

Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, Hematology and Oncology

Paul Kaesberg, M.D.

Paul Kaesberg, M.D.

Professor of Internal Medicine, Hematology and Oncology

Aaron Rosenberg, M.D.

Aaron Rosenberg, M.D.

Associate Professor of Internal Medicine, Hematology and Oncology

Joseph M. Tuscano, M.D., Ph.D.

Joseph M. Tuscano, M.D., Ph.D.

Professor of Internal Medicine, Hematology and Oncology

Jeanna Welborn, M.D.

Jeanna Welborn, M.D.

Professor of Medicine, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Medical Director, Adult Infusion

Theodore Wun, M.D., FACP

Theodore Wun, M.D., FACP

Associate Dean for Research

Director of the UC Davis Clinical and Translational Science Center

Chief, Hematology and Oncology

Professor of Medicine, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

Pediatric Hematology and Oncology

Arun Ranjan Panigrahi, M.D.

Arun Ranjan Panigrahi, M.D.

Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, Hematology and Oncology

Anjali Pawar, M.D.

Anjali Pawar, M.D.

Medical Director of the Pediatric Infusion Center

Associate Professor of Clinical Pediatrics

Radiation Oncology

Megan Daly, M.D.

Megan Daly, M.D.

Assistant Professor

Ruben Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D.

Ruben Fragoso, M.D., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Shyam Rao, M.D., Ph.D.

Shyam Rao, M.D., Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Richard Valicenti, M.D., M.A., FASTRO

Richard Valicenti, M.D., M.A., FASTRO

Professor

Department Chair of Radiation Oncology

Dietitians

Danielle Baham, M.S., R.D.

Danielle Baham, M.S., R.D.

Kathleen Newman, R.D., C.S.O.

Kathleen Newman, R.D., C.S.O.

Genetic Counselors

Social Work

LaKeisha Pitts, L.C.S.W.

LaKeisha Pitts, L.C.S.W.

The types of leukemia can be grouped based on how quickly the disease develops and gets worse. Leukemia is either chronic (which usually gets worse slowly) or acute (which usually gets worse quickly):

- Chronic leukemia: Early in the disease, the leukemia cells can still do some of the work of normal white blood cells. People may not have any symptoms at first. Doctors often find chronic leukemia during a routine checkup - before there are any symptoms.

Slowly, chronic leukemia gets worse. As the number of leukemia cells in the blood increases, people get symptoms, such as swollen lymph nodes or infections. When symptoms do appear, they are usually mild at first and get worse gradually. - Acute leukemia: The leukemia cells can't do any of the work of normal white blood cells. The number of leukemia cells increases rapidly. Acute leukemia usually worsens quickly.

The types of leukemia also can be grouped based on the type of white blood cell that is affected. Leukemia can start in lymphoid cells or myeloid cells. Leukemia that affects lymphoid cells is called lymphoid, lymphocytic, or lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia that affects myeloid cells is called myeloid, myelogenous, or myeloblastic leukemia.

There are four common types of leukemia:

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): CLL affects lymphoid cells and usually grows slowly. It accounts for more than 15,000 new cases of leukemia each year. Most often, people diagnosed with the disease are over age 55. It almost never affects children.

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): CML affects myeloid cells and usually grows slowly at first. It accounts for nearly 5,000 new cases of leukemia each year. It mainly affects adults.

- Acute lymphocytic (lymphoblastic) leukemia (ALL): ALL affects lymphoid cells and grows quickly. It accounts for more than 5,000 new cases of leukemia each year. ALL is the most common type of leukemia in young children. It also affects adults.

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML): AML affects myeloid cells and grows quickly. It accounts for more than 13,000 new cases of leukemia each year. It occurs in both adults and children.

This overview provides information about the major forms of leukemia. More information about each leukemia type can be found at the National Cancer Institute:

- Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

- Adult Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Childhood Acute Myeloid Leukemia/Other Myeloid Malignancies

- Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia

- Hairy Cell Leukemia

Sources: National Cancer Institute and UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center

Nicole Mans, M.S., L.C.G.C.

Nicole Mans, M.S., L.C.G.C.