Frequently asked questions about epilepsy

FAQS AT A GLANCE

FAQS AT A GLANCE

What are the different types of epilepsy?

How can I help control my seizures?

What is an electroencephalogram (EEG)?

Who is a candidate for epilepsy surgery?

Who is not a candidate for epilepsy surgery?

What is invasive video EEG monitoring?

What is involved in intra-operative testing?

What is a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan?

What is temporal lobe epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by recurrent seizures. A seizure is a brief alteration of consciousness (level of awareness), muscle control, behavior or sensory perception. Seizures can last a few seconds to several minutes. Most seizures last less than two minutes.

During a seizure, brain cells behave abnormally and show unusual repeated electrical discharges. This often begins within a small cluster of abnormal nerve cells and spreads to involve normal cells in other areas of the brain. People who suffer a single, isolated seizure are not epileptic and might not require treatment unless the seizures recur.

Seizures can be a brief interruption of brain activity (an absence seizure) or more intense and dramatic, including falling or abnormal muscles movements. (Click here to go to the Epilepsy Foundation of American Web site for a description of seizure types.)

During a seizure, patient behavior depends on the area of the brain involved by abnormal electrical discharges in nerve cells. Different areas of the brain control different body activities. The altered brain activity results in either increased or decreased activity in the part of the body controlled by the affected brain cells.

Virtually anything that alters brain function can cause abnormal brain-cell function leading to a seizure. Various injuries to the brain, brain tumors, inherited tendency for seizures, developmental abnormalities of the brain and brain infections can cause seizures. Sometimes, despite sophisticated testing, the cause of epilepsy remains unknown. Seizures can affect anyone at any age, from newborns to senior citizens.

Seizure frequency and severity can be increased by physical and emotional stress, sleep deprivation, illness accompanied by fever, certain drugs and alcohol withdrawal. Women sometimes experience an increase in seizures during menstruation.

Before treatment begins, physicians usually obtain an electroencephalogram (EEG). EEGs help to diagnose epilepsy, identify the type of epilepsy and identify the location in the brain where seizures start. EEGs show electrical activity in the brain and can show abnormal brain-cell function associated with epilepsy when the patient is not having seizures. It should be stressed that up to 50 percent of individuals with seizures might have normal EEGs between recurrences. Some patients will need an imaging study of the brain such as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Before treatment begins, physicians usually obtain an electroencephalogram (EEG). EEGs help to diagnose epilepsy, identify the type of epilepsy and identify the location in the brain where seizures start. EEGs show electrical activity in the brain and can show abnormal brain-cell function associated with epilepsy when the patient is not having seizures. It should be stressed that up to 50 percent of individuals with seizures might have normal EEGs between recurrences. Some patients will need an imaging study of the brain such as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, an antiepileptic drug (AED) may be prescribed. Sometimes more than one drug is needed, but in many cases these medications are successful in controlling seizures. A neurologist can assist primary care physicians in determining the right medication or combination of drugs. A patient with seizures that do not improve after a reasonable treatment period, typically a few months, should be seen by a neurologist who specializes in treating epilepsy.

When medications fail, some patients are good candidates for epilepsy surgery. Patients whose seizures begin in a well-defined area of the brain that is not too close to important brain functions, such as language, are good candidates for surgery.

Some people experience psychogenic seizures (seizure-like behavior without abnormal brain activity). In these patients repeated EEG tests show no abnormality, even during the event. These seizures are often caused by stress and can be disabling. Seizure medicines (AEDs) are not effective, but psychotherapy is another alternative.

It's important that prescribed antiseizure medicine is taken exactly as directed. Some medications such as ethosuximide and phenobarbital can be taken once a day. Other medications must be taken several times a day to be effective. If medication in the blood is too high or too low, it can fail to control seizures or it can produce unwanted side effects, such as an increase in seizure frequency.

Keeping a seizure record can also be useful for diagnosis and following the effects of new treatment.

Although leading a normal life is encouraged, activities should be avoided that present special hazards to patients and their surroundings. Patients should practice common sense, including not swimming or showering alone, bathing in a deep tub, operating heavy machinery, working at heights and participating in some sports, such as climbing.

Driving restrictions vary among states, so patients should know the law and follow a doctor's advice. In some states, the physician is required by law to inform the licensing authorities when the patient has lapses of consciousness (Find out more at the California Department of Motor Vehicles Web site).

It's important that prescribed antiseizure medicine is taken exactly as directed. Some medications such as ethosuximide and phenobarbital can be taken once a day. Other medications must be taken several times a day to be effective. If medication in the blood is too high or too low, it can fail to control seizures or it can produce unwanted side effects, such as an increase in seizure frequency.

It's important that prescribed antiseizure medicine is taken exactly as directed. Some medications such as ethosuximide and phenobarbital can be taken once a day. Other medications must be taken several times a day to be effective. If medication in the blood is too high or too low, it can fail to control seizures or it can produce unwanted side effects, such as an increase in seizure frequency.

Keeping a seizure record can also be useful for diagnosis and following the effects of new treatment.

Although leading a normal life is encouraged, activities should be avoided that present special hazards to patients and their surroundings. Patients should practice common sense, including not swimming or showering alone, bathing in a deep tub, operating heavy machinery, working at heights and participating in some sports, such as climbing.

Driving restrictions vary among states, so patients should know the law and follow a doctor's advice. In some states, the physician is required by law to inform the licensing authorities when the patient has lapses of consciousness (Find out more at the California Department of Motor Vehicles Web site).

Not every patient with epilepsy can be helped by epilepsy surgery. Fairly standard criteria must be met before surgery can be considered:

- Epilepsy that continues despite adequate trials of antiepileptic medication

- Seizures must be disabling

- Seizures must start in a region of brain that can be removed safely; patients with generalized seizures that involve large regions of both sides of the brain are not surgical candidates

If patients meet the criteria, they will need to be evaluated by an epileptologist, a neurologist specializing in epilepsy at a center that has the necessary expertise. During the evaluation, a patient might need a variety of tests to provide further information, such as neuropsychological testing, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning, video EEG monitoring and, possibly, surgical implantation of electrodes. The final decision to proceed with epilepsy surgery is made by the patient and a team consisting of an epileptologist, neurosurgeon, neuroradiologist and neuropsychologist.

Despite meeting the above criteria for epilepsy surgery, some patients may not qualify. These patients include those with co-existing severe medical illnesses, children with degenerative or metabolic diseases or patients with severe psychiatric illnesses. Depression is frequent in patients with disabling seizures and will need to be adequately treated before surgery.

This is done when a patient's seizures fail to respond to treatment, and the doctor wants to confirm diagnosis or determine if brain surgery can treat seizures. For this test, the patient is admitted to the hospital and has an EEG and video recorded continuously to capture actual seizure events (ictal EEG). These techniques are used to record information on brain function and behavior during seizures. This information is used to diagnose the type of seizure the individual experiences and, therefore, might help with prescribing medicine. This monitoring is especially helpful in difficult cases.

After admission to the monitoring unit, the patient's seizure medication may be reduced so seizures can be captured in a reasonable time period. Usually, patients are admitted to the epilepsy monitoring unit for a few days. However, recording for a week or two might be required to capture a sufficient number of seizures.

Sphenoidal electrodes are thin wires, which ends are placed near the base of the skull to record EEGs in patients suspected of having temporal lobe epilepsy. Because the skull is not opened, placement of sphenoidal electrodes carries fewer risks.

Invasive monitoring is performed in candidates for epilepsy surgery when video-surface EEG does not provide enough information about the location of the seizure focus. This might happen when the seizure focus is deep within the brain and a recordable EEG seizure discharge is not present at the scalp. In invasive monitoring, electrodes are placed on the brain surface or within various brain regions to record these small signals.

Strips or patches of thin metal electrodes are placed on the surface of the brain in a surgical operation. Depth electrodes might be implanted within the brain substance to record from deep brain structures. Implanting electrodes is a neurosurgical procedure and informed consent is obtained from each patient before surgery. These procedures carry some risk. However, invasive monitoring might provide the information needed for performing curative epilepsy surgery in patients with disabling seizures.

The intracarotid amobarbital test or Wada test is part of the pre-surgical evaluation in patients considered for epilepsy surgery. A thin plastic tube is inserted under local anesthesia into an artery at the groin and threaded into the carotid artery in the neck. A short-acting anesthetic agent is injected into the carotid artery. Each half of the brain is put to sleep for a few minutes. During that time, the patient's ability to speak, understand speech and memory is evaluated. After the medication wears off, the process is repeated with the other hemisphere. The Wada test determines which cerebral hemisphere is "dominant" for speech, and if memory is functional on one or both sides of the brain. The test takes a few hours and patients usually go home the same day.

During epilepsy surgery, testing can be done to localize specific brain regions. This guides surgeons and allows them to obtain the best possible results. Some areas of the brain can be removed without apparent ill effects. However, there are some areas which removal could cause neurological deficits such as paralysis, or speech and language problems. Intra-operative testing helps guide the surgeon to avoid these critical brain regions.

During surgery, stimulation of the brain with very small electrical currents is used to locate motor cortex and cortical speech centers. Stimulation of a speech center interferes with speech or comprehension of written or spoken language; the patient must be awake during such testing. If speech is on the same side of the brain where epilepsy surgery is to be performed, mapping of the brain while the patient is awake might be needed before an epileptic focus is surgically removed. The patient is put to sleep when a portion of the skull bone is removed and then allowed to wake up. The brain is insensitive and can be electrically stimulated without causing discomfort.

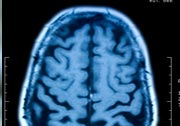

The MRI scan gives us a high-resolution image of the brain. In conjunction with other tests it can help localize the brain region responsible for the patient's seizures. In patients with certain types of epilepsy, the MRI abnormalities can be fairly subtle. The expertise of a neuroradiologist trained to detect these abnormalities is often needed. In patients with suspected temporal lobe epilepsy, special MRI techniques are needed to maximize the probability these abnormalities will be detected.

The MRI scan gives us a high-resolution image of the brain. In conjunction with other tests it can help localize the brain region responsible for the patient's seizures. In patients with certain types of epilepsy, the MRI abnormalities can be fairly subtle. The expertise of a neuroradiologist trained to detect these abnormalities is often needed. In patients with suspected temporal lobe epilepsy, special MRI techniques are needed to maximize the probability these abnormalities will be detected.

The most common epilepsy in adults for which surgery is performed is temporal lobe epilepsy (complex-partial seizures, psychomotor epilepsy). Many of these patients have had febrile convulsions as a child. In temporal lobe epilepsy, the seizures often start with an aura. The onset of convulsions might begin with a strange sensation in the stomach, a feeling of fear, déjà vu or hallucinations. During seizures, patients might lick their lips, move their limbs repetitively or hold them in unusual postures. Patients will not act or respond normally during these episodes. They could remain partially conscious or lose total consciousness.

Temporal lobe epilepsy is most commonly associated with a "scar" in a region of the brain called the hippocampus, or mesial temporal sclerosis. Seizures stop in more than 70 percent of patients when this lesion is removed. Some of these patients can stop medications after a couple years. Another 10 to 20 percent of patients can improve from surgery but will continue to have some seizures. Some patients might not improve significantly. Some patients might notice difficulty remembering words or recognizing places after the surgery, but these deficits are minor and often transient. The risk of serious complication following surgery is less than 2 percent.

Patients with intractable epilepsy should be identified, referred and evaluated for epilepsy surgery early. If not, years of recurrent seizures can cause harmful effects and should be avoided. Two years is the recommended limit for ineffective drug therapy.

In some patients with long-standing epilepsy, the cause of the seizure may be slow-growing tumors, vascular malformations (an abnormal clump of blood vessels in the brain), infections or congenital abnormalities. These lesions are picked up on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. Removal of a lesion may cure a patient's epilepsy. These patients are best evaluated at a comprehensive epilepsy center.

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is indicated in adults and children who are not candidates for potentially curative surgical resections. These patients have medically intractable partial seizures. VNS rarely causes complete seizure remission. The degree of control with VNS appears to be similar to the newer anticonvulsants. The vagal nerve stimulator (VNS) is a small disc about the size of a small hockey puck that is surgically implanted under the skin on the chest wall or in the arm pit. A tiny wire is burrowed under the skin of the chest to the neck where the wire is attached to a nerve in the neck (the vagus nerve). The stimulator turns on for about 30 seconds every 5 minutes. Over time the current which passes up the vagal nerve to the brain will reduce the number and intensity of seizures in about 40-60% of patients. The surgery is done under general anesthesia and often the person goes home the same day.

The ketogenic diet is a special treatment for epilepsy in children and young adults. This strict diet is less effective in adults and must be monitored by a neurologist and a dietitian. The diet is high in fat and low in carbohydrates (sugars). Patients on the diet should not cheat, such as eating a candy bar, because it could cause seizures. The diet is effective in reducing seizure frequency or completely stopping seizures in about 50 percent of patients.

Until recently, neurologists classified the types of seizures, such as focal or generalized convulsive. The past few decades, research has leaned toward determining if the patient has an epileptic syndrome, or a specific type occurring under certain conditions. These conditions could include a particular clinical setting at a certain age with other accompanying findings like radiological tests and EEGs.

Absence — or petit mal — seizures can illustrate the value of a syndrome approach. Absence seizures are distinct seizures with a characteristic EEG pattern (the three-second spike and wave discharge). They usually occur in otherwise normal individuals, start in some children around 3 or 4 years of age, are usually not associated with another seizure type and disappear by the early teens. The children are otherwise normal and all the radiological studies (MRI) are normal.

Another group of children will begin having absence seizures around ages 8 to 10, then develop myoclonic seizures (brief muscle jerks, usually in the mornings) around 10 to 12 years old and generalized tonic-clonic ("grand-mal") seizures in their mid-teens. These children will have seizures all their lives.

Both groups of normal children have absence seizures but the first (childhood absence epilepsy syndrome) will often outgrow their seizures and respond to ethosuximide whereas the second group have the juvenile myoclonic epilepsy syndrome and have lifelong seizures. They usually respond better to valproic acid or lamotrigine.

There are many epileptic syndromes; several have been found to be caused by a gene defect. Future research might provide a genetic cause for many other syndromes and, more importantly, divulge the chemical defect in the body caused by the defective gene which might be repairable.