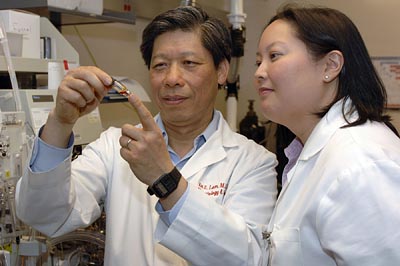

Vera Go is using combinatorial chemistry methods developed by Kit Lam to identify new treatments for cytomegalovirus — or CMV.

Posted July 28, 2010

Vera Go’s medical career started like many others: “Washing dishes!” She laughed and explained that as a biochemistry major at UC San Diego, getting your foot in the laboratory door can start off with washing laboratory glassware.

“It's a job,” she added, “but you get a chance to see research up close and interact with scientists.”

It was an unassuming start to a now-auspicious career. In addition to washing dishes as an undergraduate student, Go also assisted a UC San Diego professor in his research on CMV, or cytomegalovirus, and hearing loss. While volunteering for the pharmacy home infusion service at UC San Diego Health System, she made a lot of foscarnet IVs for treating patients with CMV infections. Those experiences ignited her interest in the virus and led to her research today: developing a targeted anti-CMV drug.

After UC San Diego, she went “sideways” geography-wise to attend New York Medical College and then earn her Ph.D. in viral oncology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York. But Go, who grew up in Walnut Creek, wanted to come back to Northern California, and UC Davis was her primary destination.

“It was just a feeling during my residency interviews that Davis was right for me,” she said. “Everyone was collegial and down to earth. I liked its potential and diversity.”

“It is wonderful to have such an enthusiastic trainee so dedicated to developing a laboratory-based research career.”

“It is wonderful to have such an enthusiastic trainee so dedicated to developing a laboratory-based research career.”

— Richard Pollard

She completed her residency in internal medicine and fellowship in infectious diseases at UC Davis. Currently, she’s completing an additional fellowship through the Mentored Clinical Research Training Program – offered through the health system’s Clinical and Translational Science Center – which provides promising new investigators with opportunities to conduct patient-centered translational research and sets the groundwork for long-term collaborations. As such, she works in both the clinic and the lab.

“I function as a staff physician, seeing patients in our hospital and clinics,” she said.

She treats patients with a variety of viral, fungal and bacterial infectious diseases, ranging from HIV and tuberculosis to osteomyelitis and valley fever. But in the lab, she focuses on CMV.

A complex, intriguing virus with a range of outcomes

CMV’s ubiquity combined with the mystery of how little is truly known about it are especially intriguing for her.

“It’s a very complex virus that can live symbiotically with you and not cause a single problem during your lifetime,” Go said. “But if your immune system becomes compromised, it can wreak havoc.”

About the Division of Infectious Diseases

UC Davis Health System clinicians provide primary-care and consultant services for all major infectious diseases and serve as valuable resources for the public-health community. Division physicians provide care for Sacramento-area HIV patients in partnership with the Center for AIDS Research Education Services (CARES), where patients have access to state-of-the-art treatment as well as clinical trials of new therapies. Also offered are a broad spectrum of diagnostic and therapeutic services, including immunizations for those traveling to exotic locales and treatment for emerging infections such as Lyme disease. For more information, visit the division’s website.

CMV is part of the herpes family, which also includes chicken pox and herpes simplex. The virus spreads through person-to-person contact, for instance via sexual contact, blood infusions, pregnancy, or simply by shaking hands and then touching the eyes or the insides of the nose or mouth. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that between 50 and 80 percent of adults are infected with CMV by age 40 and more than 90 percent are estimated to be exposed by age 80.

Like other herpes viruses, CMV has periods of activity and inactivity. It can remain dormant for years in a healthy body, never causing obvious illness. Others experience mononucleosis-like symptoms, gastrointestinal problems or pneumonitis. It is especially dangerous, however, for the very young, transplant recipients, chemotherapy patients or people with AIDS.

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, CMV retinitis was considered a primary indicator of AIDS and is still a major cause of blindness in HIV patients. CMV can also cause congenital malformations and neurological disability in infants if the mother is infected while pregnant. It can also lead to organ failure among transplant patients and life-threatening infections for those with cancer.

Using combinatorial chemistry to find new approaches

Despite CMV’s prevalence, there is no vaccination or cure, and treatment options are few. The three to four currently available medications are not always effective and can be toxic. Because the virus affects a variety of cells, Go is concentrating on finding a way to limit the entry of infection altogether.

“Using combinatorial chemistry methods, I’m trying to find an inhibitor – or protector – of healthy cells that prevents CMV from ever accessing them,” she said.

Kit Lam, chair of biochemistry and molecular biology and a founder of the field of combinatorial chemistry, is Go’s faculty advisor on this work. The technique allows multitudes of compounds to be screened at one time to identify the few – or even the one – that binds to the virus so that it cannot enter a healthy cell. Such targeted treatments are likely to have few side effects.

When Go is not in the lab or caring for patients, she enjoys international travel. On a recent trip, she visited Machu Picchu in Peru.

In addition to Lam, Richard Pollard, chair of infectious diseases, and Peter Barry, professor and vice chair of research for medical pathology and laboratory medicine, serve as mentors on her CMV research – collaborations made possible through the Mentored Clinical Research Training Program. Pollard is especially encouraged by Go’s research.

“Vera’s investigations are of primary importance as her research findings may bring us closer to effective CMV treatments,” he said. “It is wonderful to have such an enthusiastic trainee so dedicated to developing a laboratory-based research career.”

Having three mentors is rewarding but involves some commuting. Go travels between the VA Northern California Health Care System in Rancho Cordova, where she sees patients; the UC Davis main campus, where she conducts research with Barry; and the UC Davis Sacramento campus, where she does both and where Pollard and Lam are located. She lives in Roseville.

“I drive a lot!” she laughed.

In her free time – what little she has – Go loves to travel internationally. She went hiking in New Zealand earlier this year and last year she visited Peru. It’s a good balance for the intensity she brings to the lab.

“Everyone knows: Every time I have vacation, I’m out of the country,” she said.